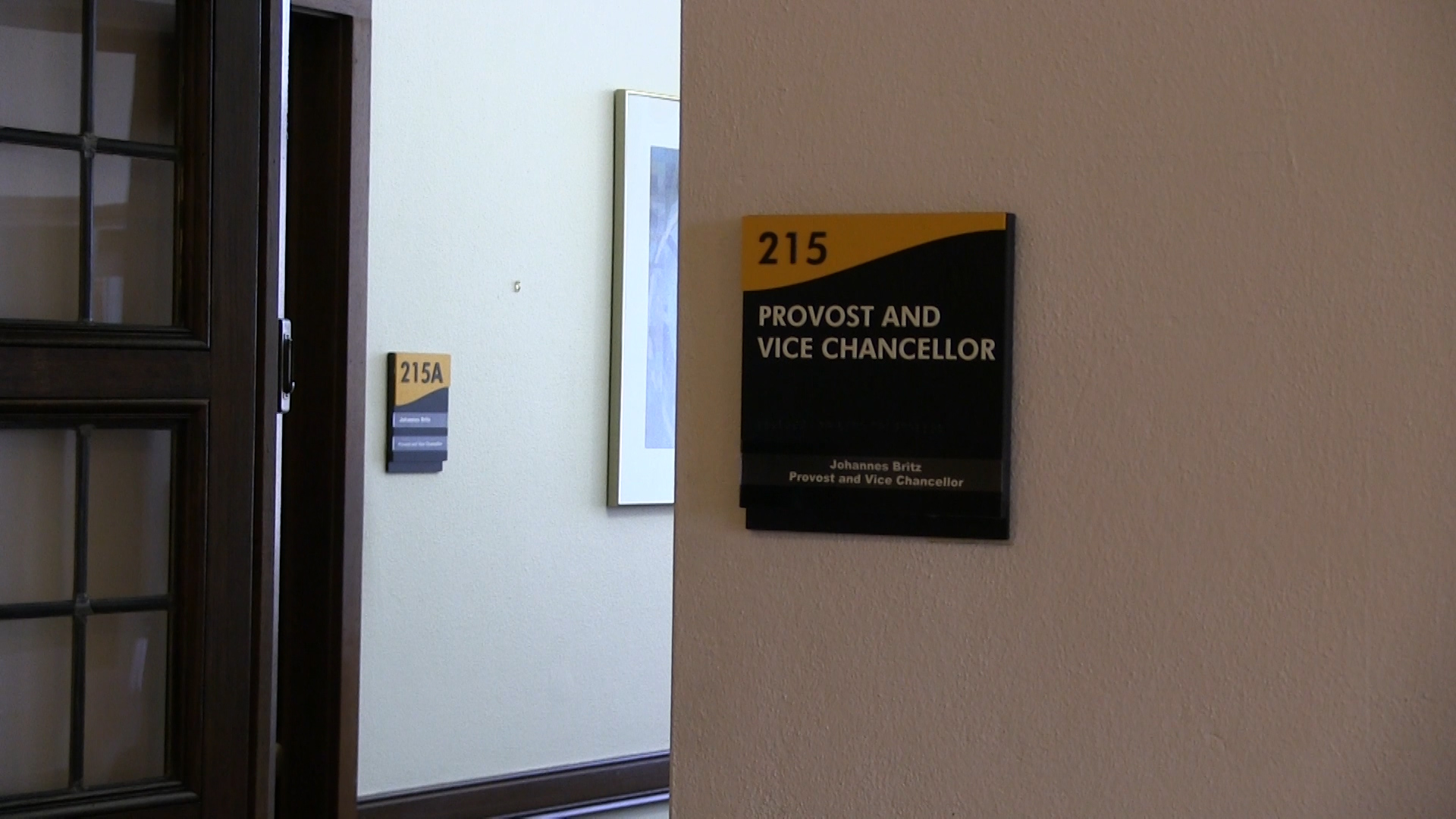

When a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee student accused her supervisor of alleged drunken texting, campus officials disagreed over whether the behavior was sexual harassment, with the Office of Equity & Diversity Services finding a violation of the discriminatory conduct policy and Provost Johannes Britz – who has the final say – ruling otherwise.

Internal documents obtained by Media Milwaukee show Britz encouraged the student, who worked on campus, to contact UWM police about her safety concerns, and EDS reached out to police supervisor Brian Switala about a possible intermediate safety measure in the student’s case, even though Switala was accused of sexual harassment in an unrelated matter not long before. Switala’s complaint was pending at the time; Britz eventually found no violation against Switala – again disagreeing with the equity investigator – on the same day the provost ruled in the student’s case. Both cases were in 2015.

In the texting case, the former student said the alleged behavior started in May of 2015, when her supervisor was accused of sending her at least 34 drunken texts in just over three hours, such as, “You are a beautiful woman,” “Gorgeous is how I would describe you. Butifule (sic) women. I can’t describe how Butifule (sic) you are,” “[s]o if you ever feel down you can always call me up and I’ll make you smile cuz you make me smile,” and “Lol . . . I’m just going to keep bugging you until you get me fired.” At one point, according to the documents, he texted the word “drunk.”

The next day, he apologized, writing “ugh…sorry about the texts,” documents show. The female student further alleged that the supervisor, who still works at UWM, then retaliated against her through a series of actions, allegedly requiring her to attend one-on-one, non-work-related meetings and showing a “weird obsession” with her whereabouts, along with other things that troubled her. “I live in constant fear of my safety,” the student told officials, the documents showed. Neither Britz nor EDS sided with the student on the retaliation angle.

However, the provost’s decision on the sexual harassment question marks the third confirmed time that Britz has ruled differently from EDS since 2015. In the student’s case and in another from 2015, he included commentary in his decision which implied that a complainant’s failure to confront a respondent immediately makes complaints less viable. The texting case documents can be read later in this story.

Enlarge

In the female student’s case, although Britz called the supervisor’s texts “entirely inappropriate,” Britz wrote that the case did not violate the university’s Discriminatory Conduct policy governing sexual harassment, in part because “the Complainant responded nine times to the Respondent’s 35 text messages. In none of her nine responses did she indicate that his texts were unwelcome or ask him to stop.”

Britz noted that the then-student wrote back “OK haha” to one text and wrote, “It’s fine really I know you were not in your normal mindset and I think we should just forget about it.” In contrast, EDS wrote, “EDS determines that there is sufficient evidence to substantiate a finding of Discrimination and Sexual Harassment against the Respondent regarding the text messages sent to the Complainant commenting on her physical appearance and gender.”

Britz’s written comments and subsequent “no violation” for sexual harassment shocked the now former student. The provost has the final say.

“I’m speechless, still, that they said that,” she said.

Astar Herndon, Wisconsin state director of 9to5, an organization that works on women’s issues, said the burden on complainants to demonstrate that such advances and behaviors are unwelcome is culturally tilted against them.

“[There’s] this unspoken thought that the woman has done something to encourage or prompt these unwanted experiences,” she said.

As Media Milwaukee uncovered in December of 2017, UWM has had 37 complaints of alleged sexual assault and harassment against professors and staff since 2013. The young woman’s case is one of those complaints.

UWM has not yet released the complaints and decisions, despite Media Milwaukee’s open records request. The student news site first requested two years of the complaints and decisions on Nov. 17, 2017 and asked for the 2015 sexual harassment complaints and decisions and all sexual assault complaints and decisions since 2013 on Dec. 28, 2017.

That request is still pending. The university says it may be legally obligated to provide notices to the accused. Media Milwaukee obtained the alleged drunken texting decisions from a source, not the university.

Britz found a “violation” in only 11 sexual harassment and sexual assault cases filed against staff since 2013 (he found “no violation” in all cases in 2015). Those details derive from a chart that the university sent Media Milwaukee.

It listed Britz’s finding for each case. Asked to provide EDS outcomes to compare how often Britz reached a different decision than the equity office’s recommendations, UWM told Media Milwaukee there was no responsive document.

UWM police contacted

Media Milwaukee previously discovered, through sources, two other instances of the provost finding no violation when EDS ruled otherwise – both also in 2015 and involving then-supervisors in the UW-Milwaukee Police Department, including former Sgt. Switala, who has since been promoted to lieutenant. It now turns out that the equity office contacted Switala in connection with the student complaint in the unrelated texting matter.

The EDS complaint in the texting case indicates that “immediately upon receiving the Complaint and meeting with the Complainant and her mother,” EDS contacted various UWM supervisors, including “UWM Police Sergeant, Brian Switala to implement Intermediate Measures to ensure a safe work environment and to limit any contact between and (sic) Complainant and the Respondent.” The complaint alleging sexual harassment against Switala was one of several involving UWM police that were made in May 2015 by anonymous people, the university has said; the unrelated texting case complaint was filed in July 2015 (the office where the student worked was not the Police Department).

“I understand that the Complainant was referred to the UWM Police Department to discuss her concerns, and I would encourage her to follow up with it if she continues to feel unsafe,” Britz wrote in the texting decision, finding of the supervisor in the texting case, “I do not see any evidence to suggest that the Respondent poses any threat or that there is a factual basis for such fear.”

Asked about the appropriateness of Switala being contacted about the student’s case when there was a complaint against him, Michelle Johnson, who is UWM’s sr. director of Integrated Marketing & Communications, told Media Milwaukee that “an EDS staff member contacted Sgt. Switala about the SAFEWALK program — which is managed by the police department — in order to refer (the student accuser) to the program. My understanding is that the referral did not result in a request for SAFEWALK services, and that was the end of Sgt. Switala’s involvement.”

She added: “According to the police chief, it is common for staff members from various campus units to contact police for information about the SAFEWALK program, and it is within the scope of police supervisors’ duties to provide background on how the program works. Sgt. Switala was a supervisor at that time. Therefore, it was appropriate for EDS to contact Sgt. Switala in this instance for this specific form of assistance.”

Enlarge

In the texting case, the young woman, who wishes to remain unnamed, provided documentation to Media Milwaukee of her complaint against the university manager who supervised her.

“I thought it was completely inappropriate,” the student said in an interview with the student news site, adding, “I graduated a year and a half ago and he was still there and there was no real push to get him out.”

Media Milwaukee is not naming the supervisor to protect the identity of the accuser. The supervisor in the case was a non-instructional supervisor of the student on campus.

In a statement to Media Milwaukee, the supervisor wrote, “As described in the aforementioned EDS complaint, I conducted myself irresponsibly. I complied and cooperated throughout the university’s investigation. UWM’s ruling outlined disciplinary requirements, which I have since completed. I have no further comment on this issue.” The EDS complaint says the man was “extremely remorseful and ashamed” and told investigators he’d been out drinking when friends when the texting occurred. However, after apologizing to the student for the texts, the supervisor allegedly wrote her again, writing, “we’ll get ice cream tomorrow, it’s on me,” documents show.

In his response letter, Britz wrote, “After reviewing the file, I am again unable to find that the Respondent’s behavior prior to the Complainant’s EDS complaint constituted harassment within the meaning of UWM’s policy or the law.”

Although he found that there was no violation, he wrote, “I agree that these texts were wholly inappropriate,” and advised that the Respondent be required to attend Title IX and professionalism training as well as have a letter placed in his file; in his conclusion, Britz added, “I commend the Complainant for bringing this matter to the University’s attention.”

EDS found that a “reasonable person would find (the text messages) intimidating and sexual in nature.” The provost wrote that he disagreed. He thought they were not intimidating or sexual in nature but were inappropriate.

“Her own text responses did not indicate that his texts were unwelcome or that she viewed them as harassing,” wrote Britz.

UWM’s Discriminatory Conduct policy says, that in order to rise to the level of harassment, the conduct must “unreasonably interfere with the individual’s work…at UWM or create a working…environment that a reasonable person would find threatening or intimidating.” According to Britz’ decision, “under applicable legal standards, an employee alleging sexual harassment based on a hostile environment must show: (1) she or he was subjected to unwelcome conduct; (2) the harassment was based on sex, and (3) the harassment was severe or pervasive so as to alter the conditions of his or her work environment by creating a hostile or abusive situation; and (4) there is a basis for employer liability.

The Allegations

Enlarge

The complainant said she initially wanted to forget the incident and move forward professionally after receiving the texts. Speaking to Media Milwaukee, she said she was 20-years-old at the time and, “need[ed] the job to live.”

However, after the text messages, she alleged that her supervisor began mandating hour-long meetings with her twice a week.

It was a pace so frequent, even his manager noticed; as the EDS report alleged: “a supervisor addressed the long meetings that he was having with the Complainant. The Respondent stated . . . that his intentions were to be a mentor to the Complainant.”

The complainant said the meetings lacked professional content and made her even more uncomfortable. In addition to this, she also alleged that he started requiring her to turn in personal projects to discuss during their meetings, although the additional work was unpaid and took time away from her job duties.

In the EDS report, her supervisor said he “encouraged” her to do personal projects to “ease the struggle with the technical aspect of her job because she had an “artistic perspective.”

However, the complainant saw them as excuses for requiring more one-on-one time with her.

“[He said], ‘If you don’t do personal work, that might affect your personal career here,’” the complainant said. “I told him that was not possible — my schedule was too rigorous.”

In the EDS report, her supervisor said he “told her to stop” the activity he had merely “encouraged” once she told him she didn’t have time for any more personal projects. However, he denied saying she might not be assigned preferred projects.

Nonetheless, at the complainant’s request, he was removed as her supervisor, and she was put under a different manager, whom she acknowledged did his best to “ease the transition.”

“Everybody knew there was something going on,” she said, “but nobody knew what.”

The Aftermath

Enlarge

The complainant alleged that the harassment continued in the form of retaliation after she filed her complaint, although neither EDS nor the provost agreed with that in their decisions.

For example, she said her supervisor allegedly violated the Intermediate Measures preventing him from assigning her any projects when he indirectly assigned her a rush order. It was noted in the EDS report that the rush order was assigned although she was not scheduled to be “on call” and additionally included how she said, “she was not provided with the ‘assets’ to complete the project within its deadline.”

The respondent also acknowledged requesting that she close out her hours on a project in the proofing stage through email correspondence with her new supervisor, which she once again interpreted as a violation of the Intermediate Measures, according to the EDS complaint.

In an amendment to her original complaint, she stated that she wanted him fired because his behavior had evolved into an alleged pattern.

“I wanted him to be fired,” she acknowledged.

In his ruling disagreeing with the student’s claims of alleged retaliation, Britz stated that her promotion was held at the request of a different employee than the respondent and that he could only recommend – not control – promotions.

Ultimately, EDS found that her supervisor had, “violated the UWM’S Discriminatory Conduct Policy (Including Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence) relating to the text messages.”

The complainant said that despite this finding, EDS’s recommendation was lukewarm.

“It is the recommendation that the Respondent attend and complete sensitivity training,” the EDS complaint read.

“I had timelines with me,” the former student told Media Milwaukee. “I had examples. [The result] was a professional growth opportunity for him,” she said.

Eleven days following her initial complaint, she appealed for more stringent action.

Provost Britz disagreed with this appeal and the EDS conclusion, writing that the allegations did not constitute sexual harassment and adding, “While these messages, in both content and number, were inappropriate, I would not characterize them as ‘intimidating,’ nor were they in any way ‘sexual in nature.’ . . . It appears that the Respondent’s inappropriate text messages caused the Complainant to view all of their subsequent interactions with suspicion.”

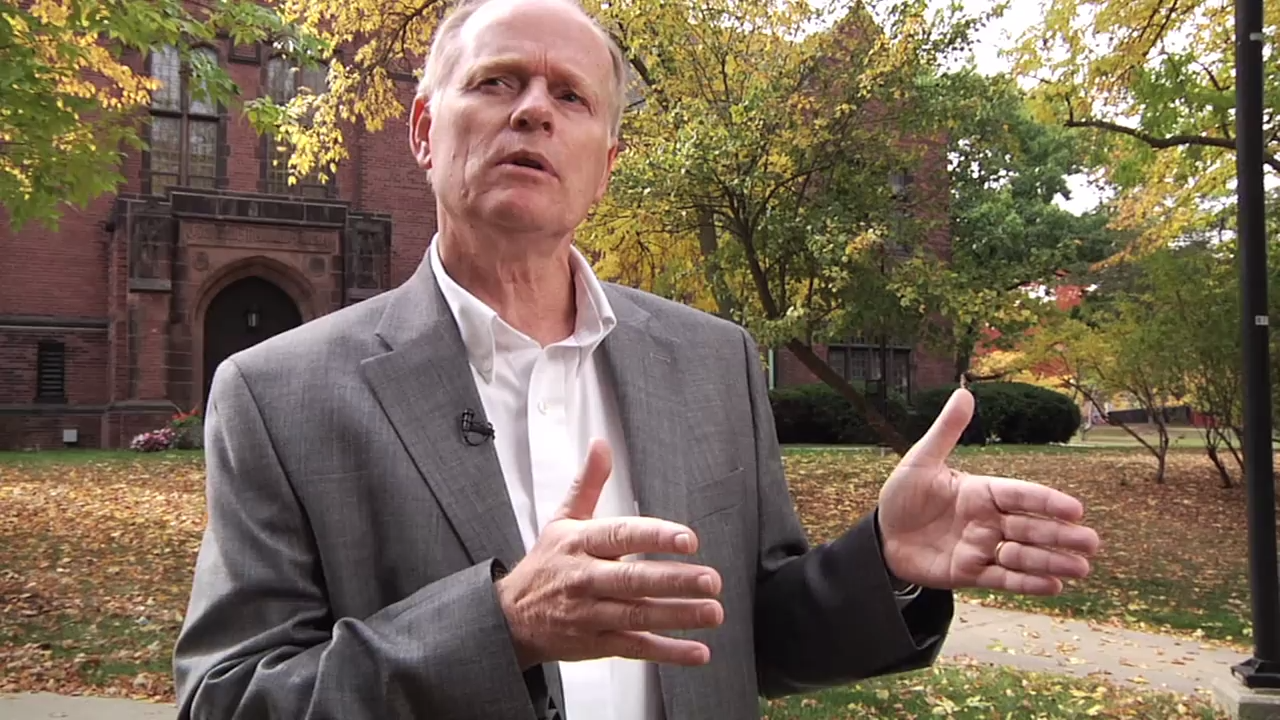

During a previous interview with Media Milwaukee, Britz said decisions he makes siding differently than EDS were “very rare.” In that earlier interview, which occurred before the student journalists obtained the texting case documents, Britz said, “My philosophy in responding to allegations of sexual harassment is first to ensure a fair and impartial process that respects the dignity and privacy of all parties. I also review investigatory findings against applicable legal standards and UWM policies and procedures.” You can read more from his interview here.

The student’s case is not the first time that Britz implied that complainants should be responsible for confronting respondents about their behavior before filing a complaint if they want those complaints to have credibility.

For example, in Switala’s case, Britz wrote, “At no point did the female officer indicate to the Respondent that she found his comments inappropriate or that he was making her uncomfortable” and “I also note that not a single witness reported telling the Respondent that they found his behavior offensive or inappropriate or that he made them uncomfortable.”

Herndon of 9to5, the national organization with state chapters dedicated to addressing workplace harassment for women, said it isn’t reasonable to expect employees to confront their supervisors, let alone make complaints, without fear of reprisal.

“I think we have enough history to show that whenever the more powerful entity feels threatened, they will use any measures to remind the less powerful entity where they are supposed to be,” she said.

Herndon also explained that the lack of distinction in regulatory efforts has made ambiguous cases more difficult to adjudicate.

“There needs to be statewide federal policies to regulate how individual businesses interpret how to deal with these situations,” she said. “Because we have not had a standardization, there is no dialogue between a micro aggression and a macro aggression.”

However, Herndon said institutions that don’t acknowledge how a power dynamic affects communication make it more difficult to resolve harassment allegations.

“We have a culture of not believing women,” she said.

In both the police officers’ cases and this one, Britz emphasized the lack of supporting evidence from third parties regarding allegations.

“Several witnesses did comment generally that the Respondent did not treat women equally. One witness indicated that s/he believed that the Respondent felt that women should not be in law enforcement, however, no information was provided to support this belief,” Britz wrote in his letter regarding a second police officer, who has now retired.

Regarding questions about the provost’s decisions, Johnson, sr. director of Integrated Marketing & Communications at UWM, said, “The provost explains his reasoning in his written decisions, and my understanding is that you have requested those decisions. That written record is the best account of his rationale for any decision.”

The student who filed the complaint has since graduated and left the university, yet she said the experience stayed with her.

“I still think about it every time a male coworker gets a little too close,” she added. “It’s been a little bit of an adjustment to kind of relearn what boundaries are acceptable in an office situation and I don’t think that’s ever going to go away.”

As to when Media Milwaukee – and the public – will be able to see the details of the other complaints? UWM’s Public Records Custodian, Julie Kipp, wrote the student journalist in November: “you should know that your request will likely trigger a statutory notice to the subjects of the request, which means even after I’ve completed the location and review, we have to give them a chance to file an injunction under Wis. Stat. 19.356(2)(a).”

However, asked for an update in February, Kipp responded that she was still “working on that request,” adding, “Further, I did not agree to inform you when I sent out the notices as I am not required to do so by law and that is not the practice of this office. I am continuing to balance this request with the hundreds of other requests this office receives and I will give you the documents in accordance with Wisconsin Open Records Law.”

If anyone has any information that would be useful to this ongoing student investigation, you can contact the student reporter Talis Shelbourne at media-milwaukee@uwm.edu.